It has taken more than a decade of research and development, but a new gene therapy appears to reverse the symptoms of Sickle Cell Anemia and is showing signs that it may be transportable to areas on the globe that are resource-challenged but where SCA is most prominent.

What is Sickle Cell Anemia

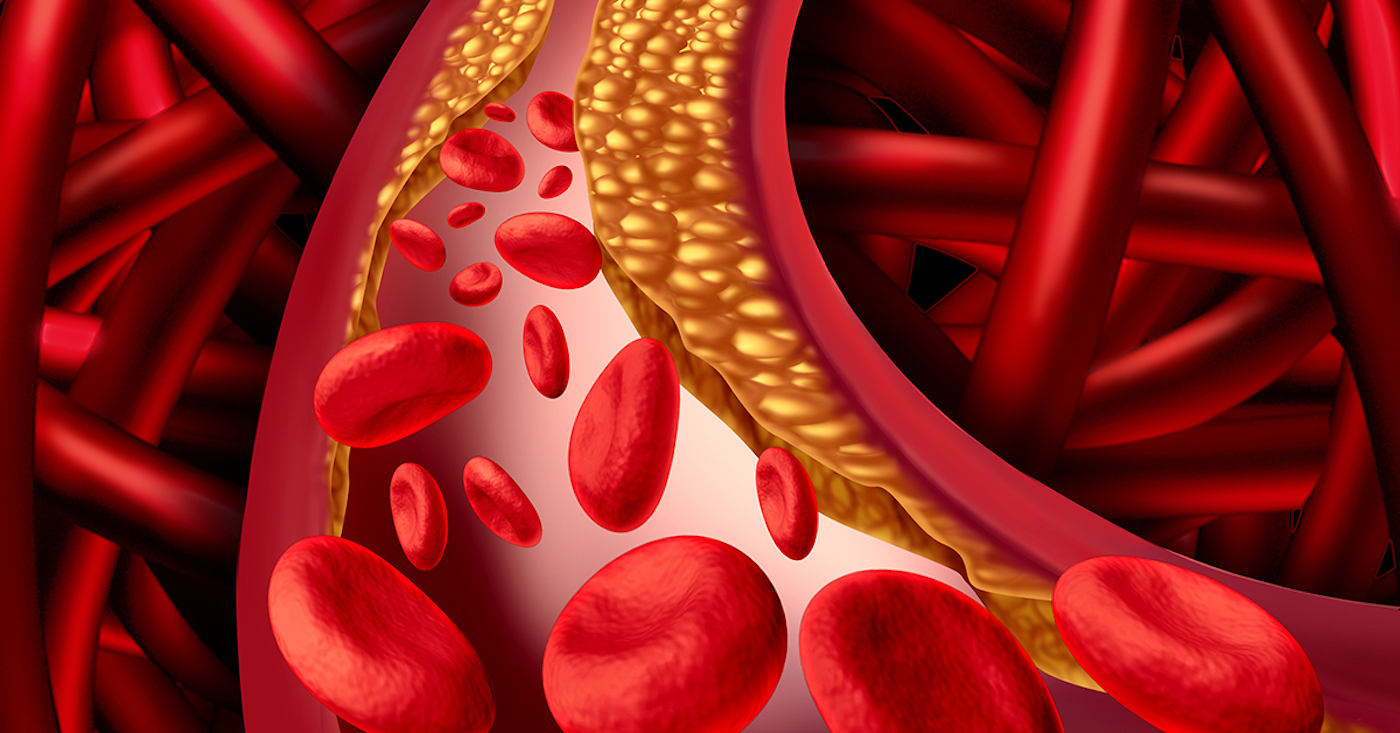

SCA is an inherited disease that causes normally flexible, round red blood cells to become sickle-shaped and rigid. These cells aren’t able to flow normally through small blood vessels and may get stuck, blocking or slowing blood flow and oxygen to critical organs, limbs, and other parts of the body.

SCA can cause significant pain as the sickle-shaped cells become trapped and block blood flow to the joints, chest, abdomen, and bones. Sometimes the pain may last for hours, but it can also continue for weeks. Your hands and feet may swell from blockages, and you may suffer frequent infections.

The condition can lead to delayed growth in infants and children and may cause vision problems if the retina because clogged with deformed cells.

New Therapy Gives Hope

According to the author of the Phase 1-2 clinical trial being conducted, two patients receiving the new therapy have seen remarkable improvements in their symptoms. The patients reported that improved quality of life. Prior to treatment, the patients, age 25 and 35, had more than a dozen acute events each year such as chronic pain, acute chest crises, pain crises, and both required oral or injectable opioid pain control regularly.

One patient experienced a single SCA event after receiving treatment and no longer requires daily opioid pain medications to control the pain, and the other patient no longer requires oral opioid pain management and has no vaso-occlusive issues, where the cells become trapped in the vascular system.

How the Gene-Therapy Works

This therapy uses a modified lentivirus vector that cannot cause illness to transfer a fetal hemoglobin gene that has been modified not to shut off (a normal fetal hemoglobin gene shuts off after birth).

Cell are collected from a sickle cell patient and genetically modified with the lentivirus. One low dose of chemotherapy is used to precondition the patient’s bone marrow, and then the patient receives their modified cells. Typically, the patient recovers from the effects of the chemotherapy within 14 days and blood counts may recover even quicker, sometimes in as little as 7 to 10 days.

Because of the reduced intensity condition required for treatment, researchers hope that hospitals in underdeveloped areas such as Central Africa will be able to offer it. Additional benefits of the treatment such as its consistency and long-term benefits may be uncovered later in the trial. Preclinical studies conducted by the researchers show that after treatment, the body is able to produce normal red blood cells instead of the sickle-shaped cells the disease is named after.

The preliminary data was presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting on December 3, 2018.